Syringomyelia and Chiari Malformation in Dogs: A Pet Parent's Guide

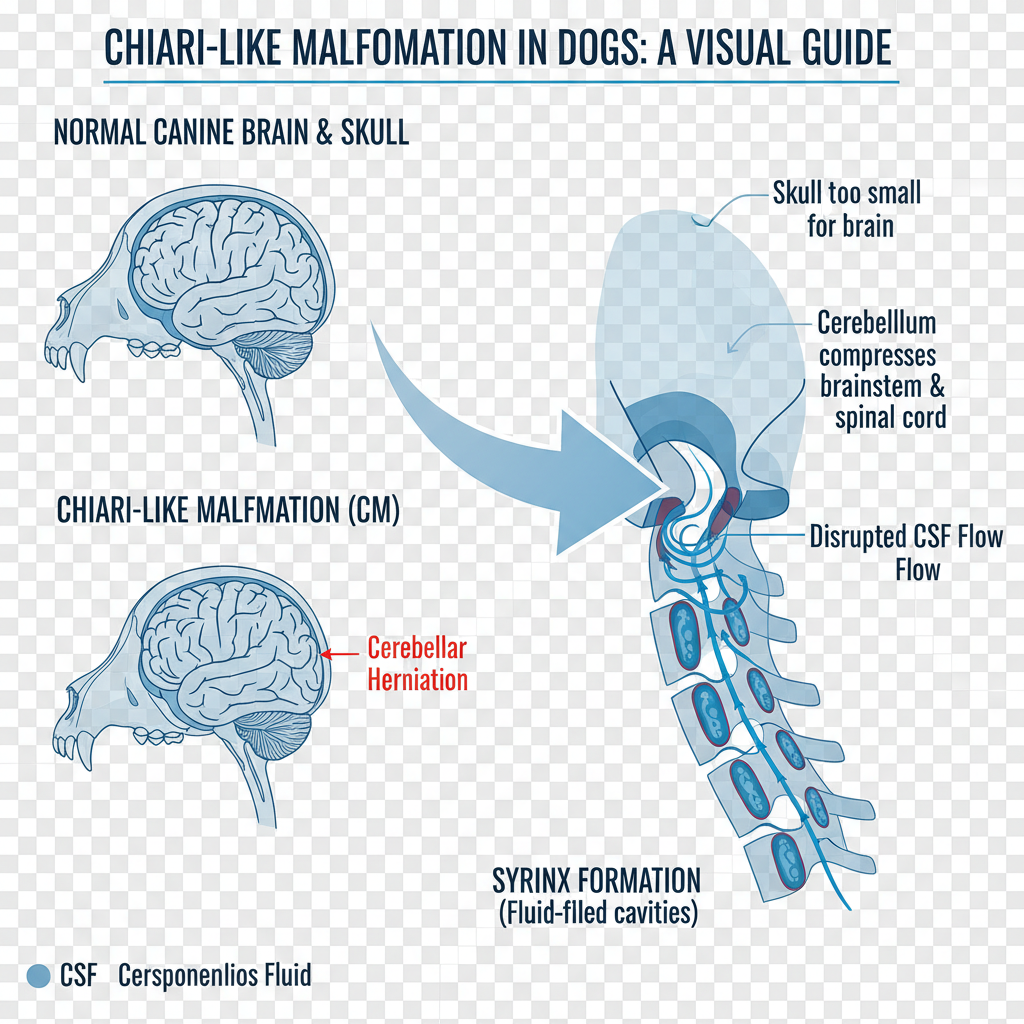

Watching your beloved dog suffer from discomfort or pain is one of the hardest parts of being a pet parent. If your pup has been diagnosed with or shows symptoms of Syringomyelia Chiari dogs, you're likely searching for answers and ways to help. This condition involves fluid-filled pockets forming in the spinal cord, often linked to a skull malformation called Chiari-like malformation. This malformation means your dog's skull is a bit too small for their brain, especially at the back, which can cause the brain to push into the spinal cord's exit point.

This crowding can mess with the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)—the clear fluid that cushions and protects your dog's brain and spinal cord. When this flow gets blocked, pressure changes can create those problematic fluid pockets, or "syrinxes," within the spinal cord tissue.

While any dog breed can get Syringomyelia (SM) and Chiari-like malformation (CM), it's most common in small breeds like Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, Griffon Bruxellois, and Yorkshire Terriers.

What Syringomyelia and Chiari Malformation Look Like in Dogs

The signs of CM and SM can vary a lot. It depends on where those fluid pockets are, how big they've gotten, how much the brain is compressed, and, of course, your individual dog. Some dogs might not show any signs at all, while others suffer from severe pain and struggle with their movement.

Here are some common signs our team at Petscarelab sees:

- Neck pain: Your dog might yelp when you touch their neck, shy away from head or neck pats, or carry their head low.

- Phantom scratching: This is a classic sign! Your dog will repeatedly scratch the air near their neck, shoulder, or ear without actually touching their skin. It's like an itch they can't reach.

- Scoliosis: In serious cases, you might notice a curve in their spine.

- Weakness or clumsiness: Especially in their back legs, making them unsteady on their feet or making jumping difficult.

- Stumbling: They might not know exactly where their paws are, leading to stumbles or their paws knuckling over.

- Personality changes: Chronic pain can make some dogs withdrawn, irritable, or less interested in playing.

- Facial weakness: This is less common but can happen if facial nerves are affected.

- Seizures: Rarely, CM/SM can trigger seizures.

These symptoms often get worse when your dog is excited, exercises, experiences temperature changes, or wears a collar.

Why Do Dogs Get Syringomyelia and Chiari Malformation?

The main reason dogs develop CM and SM is genetics. It's an inherited issue with the skull and brain shape, especially in certain small breeds. While our research is still uncovering the exact genetic details, we know it's passed down through families.

At its core, the problem is caudal fossa hypoplasia—meaning the back part of the skull isn't quite big enough. This anatomical flaw causes a chain reaction:

- Brain displacement: The cerebellum (a part of the brain) gets pushed into or through the opening at the base of the skull.

- Fluid flow blockage: This crowded space disrupts the normal flow of CSF, leading to increased pressure.

- Syrinx formation: These changes in fluid dynamics and pressure within the spinal canal cause fluid to build up and create those painful cavities in the spinal cord.

In rare instances, SM can stem from other issues like spinal injuries, tumors, or inflammation, but these are distinct from the CM-related cases we're discussing here.

How Veterinarians Diagnose Syringomyelia in Dogs

Diagnosing CM and SM in dogs involves a careful neurological exam and advanced imaging.

- Neurological Exam: Your vet will check your dog's walking, reflexes, posture, pain response, and nerve function. That "phantom scratching" is a big clue but doesn't confirm the diagnosis alone.

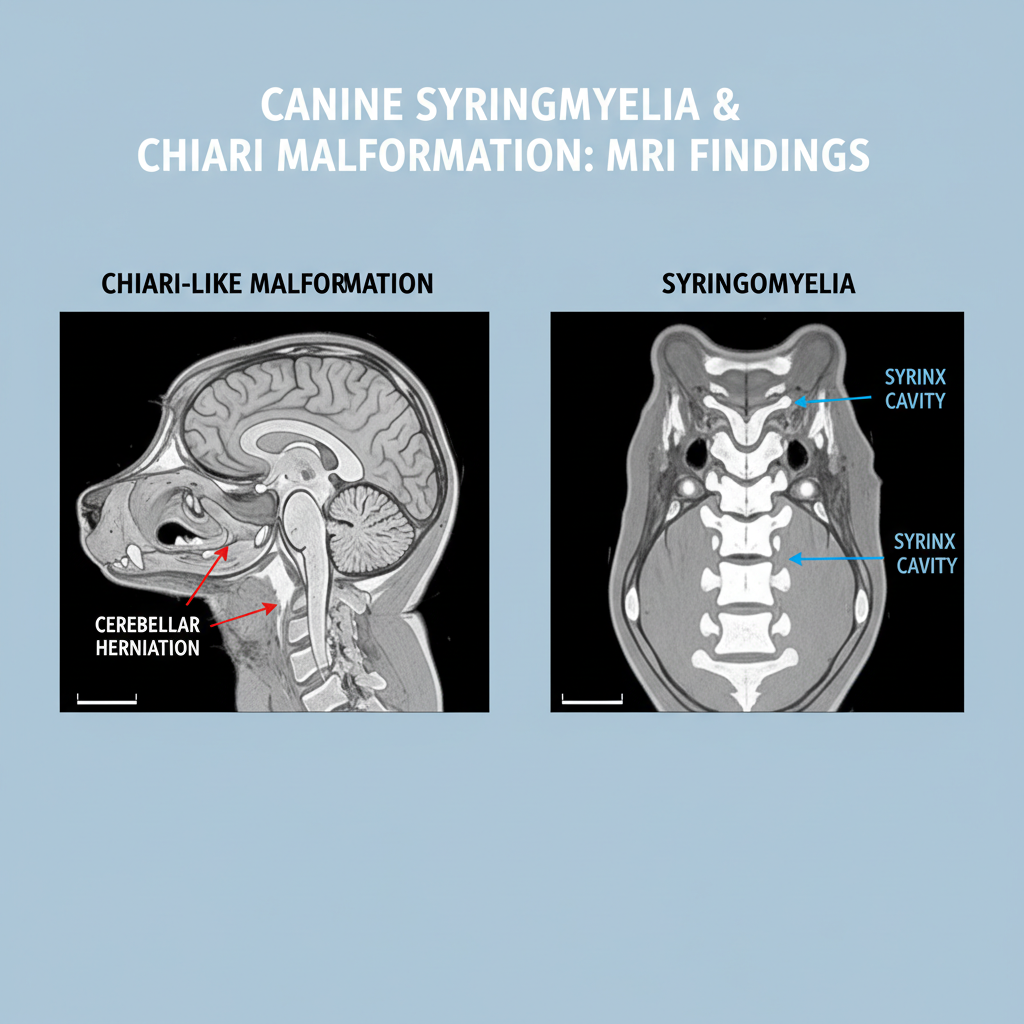

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): An MRI is the best way to diagnose both CM and SM. It gives incredibly detailed pictures of the brain, spinal cord, and bones.

- For CM, the MRI will show a smaller skull space and the cerebellum pushing into the opening at the skull's base, along with any brainstem compression.

- For SM, the MRI will clearly show those fluid-filled syrinxes in the spinal cord, detailing their size, location, and how far they extend.

Your vet might run other tests to rule out different conditions:

- X-rays: These can show bone issues but aren't enough to diagnose CM or SM.

- CT scan: Good for seeing bone, but not as clear as an MRI for soft tissues like the spinal cord.

- CSF analysis: Rarely helpful unless there's a suspicion of infection or inflammation, which isn't typical for CM/SM.

Catching this condition early is key to managing it effectively and helping your dog live a better life.

Treating Syringomyelia and Chiari Malformation in Dogs

Treating CM and SM in dogs focuses on easing pain, shrinking the syrinxes, and improving CSF flow. The best approach depends on how severe your dog's symptoms are and their overall condition.

Medical Management

For dogs with mild to moderate symptoms, we usually start with medications to manage pain and inflammation:

- Pain relievers:

- NSAIDs: Drugs like carprofen or meloxicam help with pain and swelling.

- Gabapentin: This medication is excellent for nerve pain.

- Amantadine: Can help with chronic nerve pain.

- Tramadol: An opioid-like pain medication.

- Corticosteroids: Like prednisone, these are used short-term for severe inflammation during flare-ups. Long-term use comes with serious side effects, so we avoid it.

- Diuretics: Sometimes, medications like furosemide can help reduce CSF production and pressure, which might shrink the syrinxes.

- Lifestyle changes:

- Switch to a harness instead of a collar.

- Avoid activities that make symptoms worse.

- Keep your dog at a healthy weight.

- Provide soft bedding and ramps for easier movement.

Surgical Management

If your dog has severe pain, their condition is getting worse, or medications aren't helping enough, surgery might be an option. The most common procedure is called foramen magnum decompression (FMD).

- What it is: A specialized surgeon carefully removes a small piece of bone at the back of the skull, and sometimes part of the first neck vertebra. This relieves pressure on the brain and spinal cord, allowing CSF to flow normally again.

- Why we do it: The goal is to open up that crowded area, let the CSF flow freely, stop syrinxes from getting bigger, and potentially shrink existing ones.

- What to expect: Surgery can bring significant pain relief and improve movement for many dogs. However, some dogs might still have symptoms, and syrinxes can sometimes return or worsen. Deciding on surgery is a big decision and involves weighing the risks against the potential benefits carefully.

Life After Treatment

No matter the treatment path, ongoing care is vital:

- Regular vet visits: Keep up with check-ups to monitor symptoms and adjust medications.

- Physical therapy: If your dog has weakness or trouble with coordination, physical therapy can help them build muscle and move better.

- Acupuncture: Some pet parents find acupuncture helpful for managing pain.

- Adjust their home: Continue using a harness and make sure their environment is comfortable and safe.

Our team at Petscarelab is always following the latest research into SM and CM, aiming to better understand the genetics, the underlying problems, and develop even more effective treatments for this challenging condition.