Epilepsy in Dogs: A Guide for Pet Parents

Epilepsy in dogs is a serious brain disorder that causes repeated seizures. Think of a seizure as a temporary, uncontrolled glitch in your dog's brain activity, often leading to involuntary muscle movements. While one seizure doesn't mean your dog has epilepsy, if they experience seizures again and again, it's a sign of this lifelong condition. It’s surprisingly common, affecting thousands of dogs, and it can be scary for us pet parents to witness.

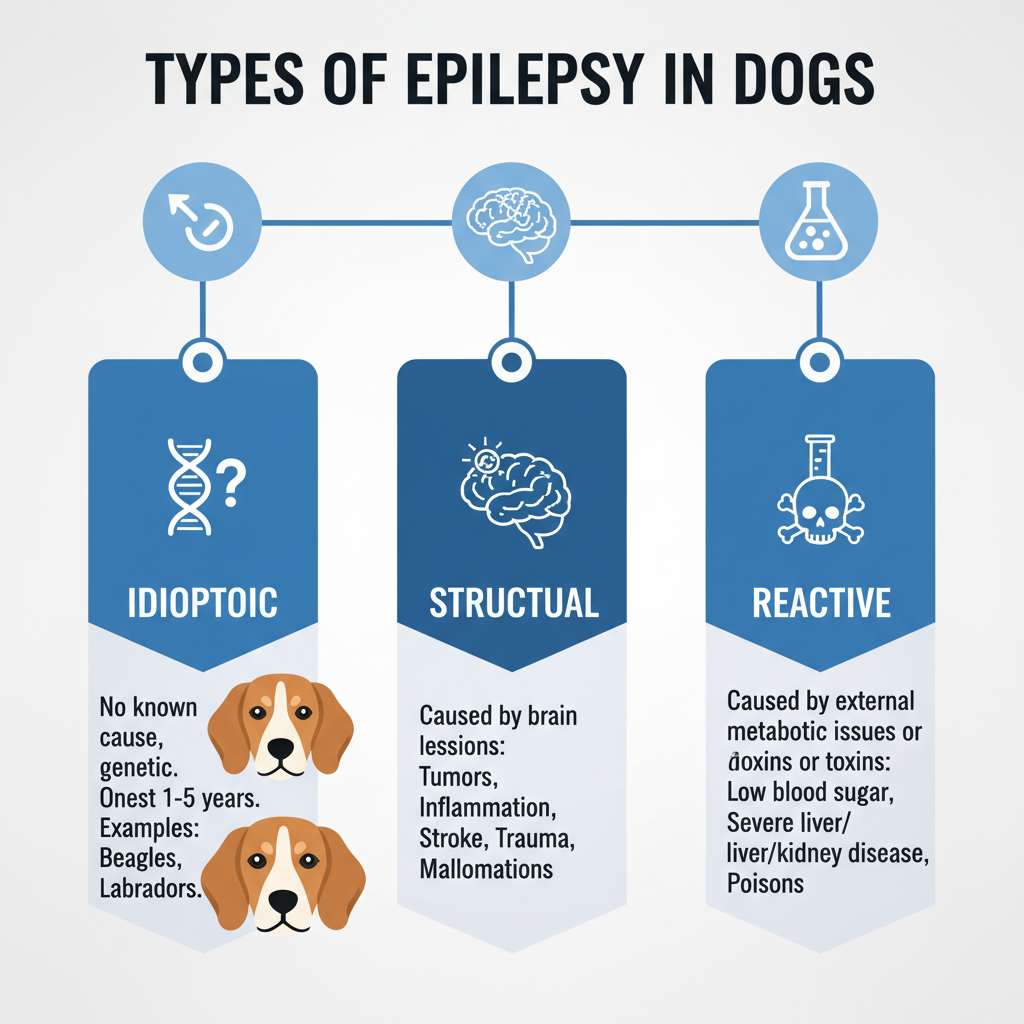

Types of Epilepsy in Dogs

Veterinary specialists classify epilepsy based on what's causing the seizures. Knowing the type helps our team at Petscarelab figure out the best way to help your pup.

Idiopathic Epilepsy

This is often called "primary epilepsy," and it's diagnosed when we can't find a clear reason for your dog's seizures. It’s like the brain just decides to misfire without an obvious trigger. This type usually shows up when a dog is between one and five years old. Certain breeds seem more prone to it, including Beagles, Bernese Mountain Dogs, Border Collies, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, German Shepherds, Irish Setters, Labrador Retrievers, and Poodles, among others.

Structural Epilepsy

Sometimes, seizures happen because there’s an actual problem with your dog's brain structure. These issues could be:

- A brain tumor, which can be benign or malignant.

- Inflammation or infection in the brain itself.

- A stroke, where blood flow to a part of the brain is cut off.

- A past head trauma or injury.

- A brain malformation, meaning the brain didn't develop quite right.

Reactive Epilepsy

This type of epilepsy isn't about the brain itself, but rather a problem outside the brain that affects its function. It’s usually caused by metabolic issues or exposure to toxins, such as:

- Low blood sugar (hypoglycemia).

- Serious liver or kidney disease.

- Exposure to poisons like lead or certain pesticides.

Symptoms of Epilepsy in Dogs

The main thing you'll notice with epilepsy is recurrent seizures. They can look different from dog to dog, but they usually follow three phases:

- Before the seizure (the 'pre-ictal' phase or aura): Your dog might act differently right before a seizure. This could mean they seem restless, anxious, try to get your attention constantly, drool a lot, or stare blankly. This phase can last anywhere from a few seconds to several hours.

- During the seizure (the 'ictal' phase): This is the actual seizure event, marked by uncontrolled muscle movements. Here's what you might see:

- Generalized ('Grand Mal') seizures: The most dramatic type. Your dog will likely lose consciousness, collapse, paddle their legs frantically, drool excessively, and may even urinate or defecate. These typically last one to three minutes.

- Focal ('Partial') seizures: Only a part of your dog's body is affected. You might see a facial muscle twitching, or they might limp or hold up a paw. Your dog might stay conscious or seem disoriented. Sometimes, a focal seizure can turn into a full-body generalized seizure.

- Psychomotor seizures: These are sometimes called "fly-biting" or "staring" seizures. Your dog might look like they're hallucinating, staring into space, or doing unusual, repetitive actions like chasing their tail for no reason.

- After the seizure (the 'post-ictal' phase): Once the seizure is over, your dog will often be disoriented. This phase can last minutes to days. They might seem weak, temporarily blind, extra thirsty or hungry, or just generally "off."

When to See a Vet

If your dog ever has a seizure, call your veterinarian right away. If you can, try to video record the seizure. This helps your vet tremendously by showing them exactly what happened.

You need emergency veterinary care if:

- The seizure lasts longer than 5 minutes.

- Your dog has multiple seizures within 24 hours (we call these "cluster seizures").

- Your dog has one seizure after another without fully recovering in between (this is "status epilepticus").

These situations are life-threatening and demand immediate medical attention. Don't wait!

Causes of Epilepsy in Dogs

As we mentioned, the causes fall into three main categories: idiopathic, structural, and reactive.

Idiopathic Epilepsy

We don't know the exact cause of idiopathic epilepsy, but our research suggests it's often genetic. Many dog breeds simply have a higher chance of developing it.

Structural Epilepsy

These seizures happen because of a physical problem in your dog's brain:

- Brain tumors: Both non-cancerous and cancerous growths can trigger seizures.

- Inflammation or infection: Things like meningitis or encephalitis can be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites.

- Stroke: When blood flow to part of the brain is interrupted, it can cause seizures.

- Head trauma: Injuries to the brain from accidents can be a cause.

- Brain malformations: Sometimes, dogs are born with parts of their brain not quite developed correctly.

Reactive Epilepsy

These causes come from outside the brain, affecting how it functions:

- Metabolic disorders: Severe liver disease, kidney disease, very low blood sugar, or imbalances in electrolytes can all trigger seizures.

- Toxins: If your dog gets into things like lead, antifreeze, certain bug killers, or rodent poisons, these can be extremely dangerous and cause seizures.

Diagnosis of Epilepsy in Dogs

Figuring out if your dog has epilepsy and what type it is involves a lot of detective work. Your vet will perform a thorough physical and neurological exam and run tests to rule out other possible causes for the seizures.

- Your Vet Will Ask All About It: Your vet needs to know everything about the seizure episodes – how often they happen, how long they last, what you saw before, during, and after. They'll also ask about your dog's general health, any medications they take, and if they might have been exposed to toxins. Remember, a video of the seizure is a huge help!

- Physical and Neurological Examination: Your vet will check your dog's overall health and look for any signs that point to a neurological problem.

- Blood Work:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): This checks for infection, inflammation, or anemia.

- Biochemistry Profile: This helps your vet evaluate organ function (like the liver and kidneys), blood sugar levels, and electrolytes.

- Thyroid levels: Sometimes, an underactive thyroid can contribute to seizures.

- Urinalysis: This simple test helps check kidney function and rules out urinary tract infections.

- Imaging:

- MRI or CT scan of the brain: These are the gold standard tests. They can show if there's a tumor, inflammation, stroke, or malformation in the brain. These often require a visit to a veterinary specialist and general anesthesia for your dog.

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) analysis: Your vet might take a sample of the fluid surrounding the brain and spinal cord (a spinal tap). They'll analyze it for signs of inflammation, infection, or unusual cells. This also requires general anesthesia.

- Other tests: Depending on where you live and what your dog has been exposed to, your vet might recommend testing for specific infectious diseases.

If, after all these tests, no underlying cause is found, your vet will likely diagnose your dog with idiopathic epilepsy.

Treatment for Epilepsy in Dogs

Our main goal when treating epilepsy in dogs is to get the seizures under control, not necessarily to stop them completely. We want to reduce how often they happen, how severe they are, and how long they last.

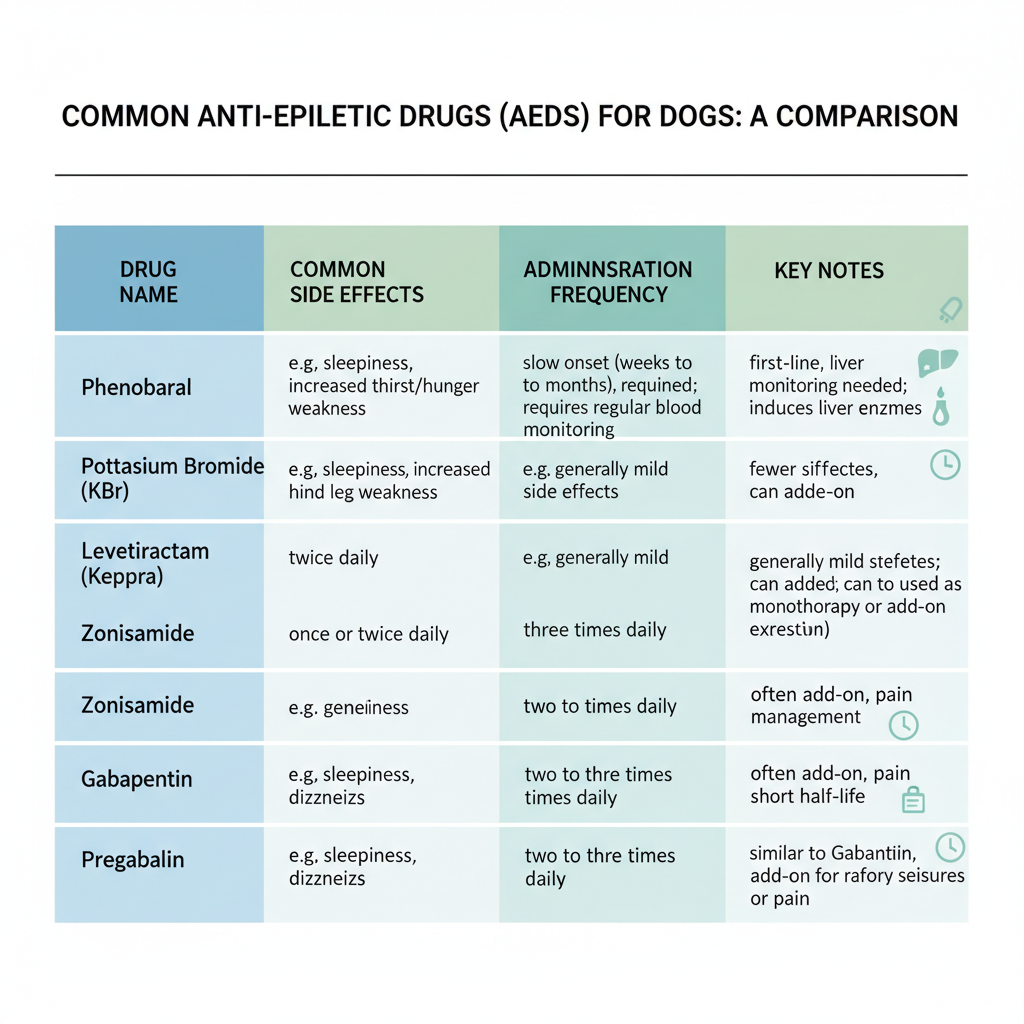

Anti-Epileptic Drugs (AEDs)

Your vet will usually decide to start your dog on anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) if:

- Seizures happen more often than every 6-8 weeks.

- They're having cluster seizures (multiple seizures within 24 hours).

- They experience status epilepticus (a seizure lasting more than 5 minutes).

- The seizures are particularly severe or go on for a long time.

- Your dog has a structural brain problem.

Here are some common AEDs:

- Phenobarbital: Often the first medication vets try. It works well, but it might make your pup sleepy, extra thirsty, or hungry. Long-term use can sometimes affect the liver, so regular blood tests are a must.

- Potassium Bromide (KBr): This often works well with phenobarbital or for dogs who can't take it. Side effects are similar to phenobarbital, plus it can sometimes cause weakness in the hind legs. It takes a few months to reach full effectiveness.

- Levetiracetam (Keppra): You can use this drug on its own or add it to other medications. It generally has fewer side effects than phenobarbital or KBr, but you usually have to give it three times a day.

- Zonisamide: Another good option, either alone or combined with other drugs. It typically has mild side effects.

- Gabapentin: Vets often use this as an add-on, especially if pain is also an issue, but it has some seizure-controlling properties too.

- Pregabalin: Works similarly to Gabapentin and is often used as an add-on.

Important Things to Remember About AEDs:

- Lifelong commitment: Most dogs with epilepsy will need medication for their entire lives.

- Stick to the schedule: Give AEDs exactly as your vet prescribes, at the same times every day. Missing doses can easily trigger more seizures.

- Regular checks: Expect regular blood tests to check drug levels and make sure your dog's liver and kidneys are healthy, especially with drugs like phenobarbital and potassium bromide.

- Never stop abruptly: Suddenly stopping or changing AEDs can lead to severe cluster seizures or status epilepticus. Always talk to your vet before making any changes.

- Watch for side effects: Be aware of any potential side effects and let your vet know right away if you see them.

Treating Underlying Causes

If your dog’s epilepsy stems from a structural problem or a reactive cause, fixing that underlying issue is crucial. This might mean:

- Surgery or radiation therapy for brain tumors.

- Antibiotics, antifungals, or anti-inflammatory drugs for infections or inflammation.

- Dietary changes or insulin for metabolic conditions like hypoglycemia.

- Detoxification if your dog was exposed to a toxin.

Emergency Treatment for Status Epilepticus or Cluster Seizures

Dogs having prolonged seizures (status epilepticus) or frequent cluster seizures need immediate veterinary help. Treatment could include:

- Intravenous medications like diazepam or midazolam to stop active seizures.

- Continuous infusions of AEDs to keep seizures at bay.

- Supportive care like IV fluids, monitoring vital signs, and keeping them from overheating.

Prognosis of Epilepsy in Dogs

The outlook for a dog with epilepsy varies quite a bit, depending on the type of epilepsy and how well it responds to treatment.

- Idiopathic epilepsy: With the right medication and consistent care, many dogs with idiopathic epilepsy can live happy lives with their seizures well-controlled. Still, don't expect seizures to vanish completely; some dogs will have occasional episodes. It’s a lifelong condition that needs ongoing management.

- Structural epilepsy: The prognosis here depends entirely on the underlying cause. Some structural problems, like certain brain tumors or severe brain damage, might have a poorer outlook. Others, like treatable infections, could have a much better outcome if caught and resolved quickly.

- Reactive epilepsy: The good news is that if we can find and successfully treat the metabolic or toxic cause, your dog often has a good chance of recovery.

What Impacts Your Dog's Outlook?

- Age when seizures started: If seizures begin very young (under 1 year old), it can sometimes mean a more severe form of the condition.

- How often and how bad the seizures are: More frequent or severe seizures can be tougher to manage.

- Cluster seizures or status epilepticus: These emergency situations can point to a more challenging case.

- Response to medication: Some dogs don't respond well to standard AEDs, meaning your vet might need to try different drugs or combinations.

Even with controlled epilepsy, your dog will need regular vet check-ups and blood tests to make sure their medication is working and not causing unwanted side effects. Living with an epileptic dog takes dedication from pet parents, but with proper care and great communication with your veterinarian, most dogs with epilepsy can lead full, joyful lives.

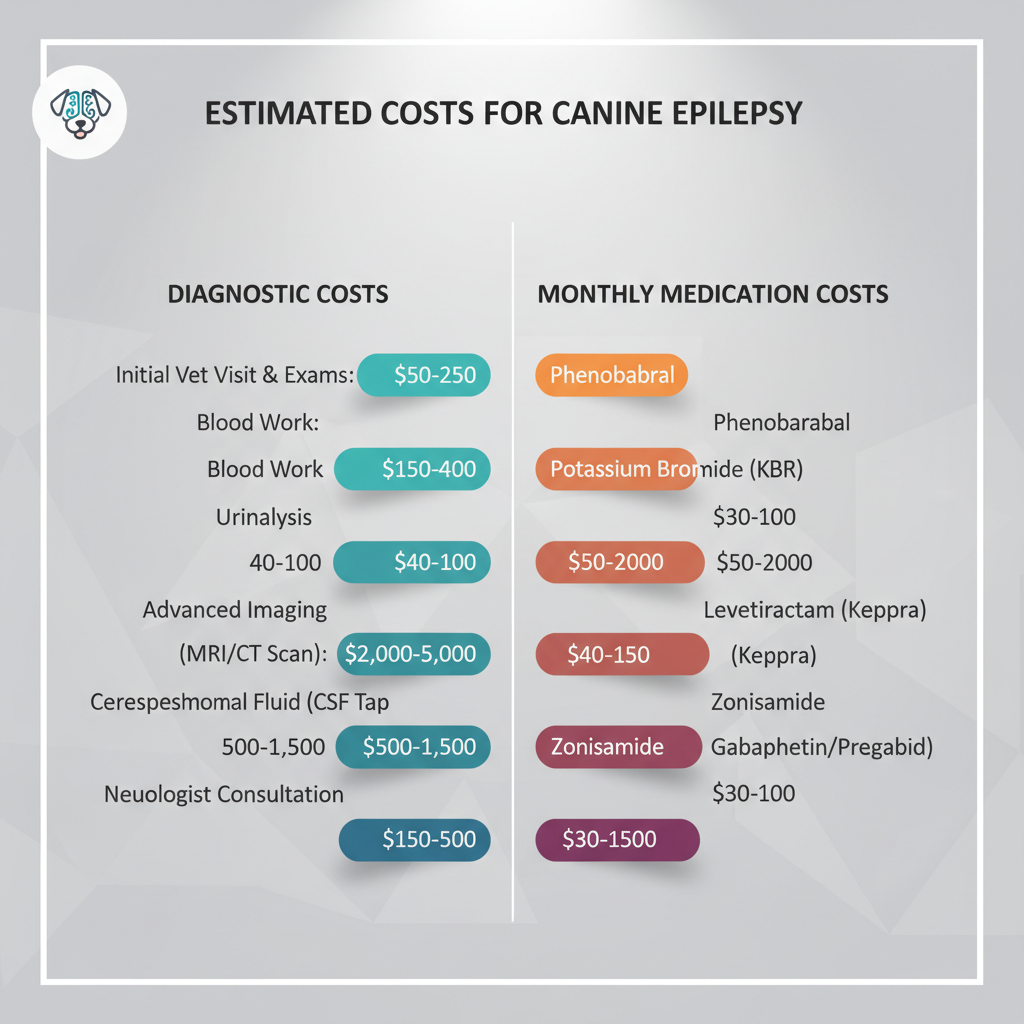

Cost of Epilepsy in Dogs

Understanding the potential costs for diagnosing and treating epilepsy in dogs is important for pet parents. Expenses can vary widely based on how severe the condition is, the type of epilepsy, your location, and the specific tests and medications your dog needs.

Diagnostic Costs:

- Initial Vet Visit & Exams: Expect to pay anywhere from $50 to $250.

- Blood Work (CBC, Chemistry, Thyroid, potentially Bile Acids): This usually runs from $150 to $400.

- Urinalysis: Typically $40 to $100.

- Advanced Imaging (MRI/CT Scan of the Brain): These are often the biggest expense, ranging from $2,000 to $5,000. They usually require a specialist referral.

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Tap & Analysis: This can cost $500 to $1,500 and also often requires a specialist.

- Consultation with a Neurologist: An initial visit can be $150 to $500.

Treatment Costs (Medication):

The monthly cost for anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) can vary:

- Phenobarbital: Generic versions might be $20 to $70 per month.

- Potassium Bromide (KBr): Around $30 to $100 per month.

- Levetiracetam (Keppra): Generics are cheaper, but it can still be $50 to $200 per month, especially since it's often given three times daily.

- Zonisamide: Expect $40 to $150 per month.

- Gabapentin/Pregabalin (often add-ons): These can add $30 to $100 per month.

Remember, many dogs need more than one medication, which increases the total monthly cost.

Monitoring Costs:

- Blood work to check drug levels and organ function (e.g., phenobarbital levels, liver enzymes): Budget $100 to $300 for these tests. Your vet will likely want them done every 3-6 months at first, then annually once your dog is stable.

Emergency Treatment Costs (for status epilepticus or cluster seizures):

- Emergency Vet Visit: An initial emergency visit can be $100 to $300.